especially true of persons whose stations are in the

lower part of the ship. However, a hit from a torpedo or

bomb or a collision with another ship may flood the

compartments normally used or knock out a ladder.

Often, some measure to control flooding taken by the

damage control party closes off the normal method of

travel.

The only answer to this situation is to know your

ship. Small ships don’t present much of a problem

because they have only a few routes you can follow.

However, large ships are another matter. Aboard an

aircraft carrier or cruiser, learning all the passageways,

doors, and ladders takes a long time. During leisure

time, learn escape routes from various below-deck

sections to the weather decks. Ask the individuals who

work in those sections the best way to get topside; then

follow that route. The time to experiment is before an

emergency occurs, not during one.

Going Over the Side

As in everything else, there is a right way and a

wrong way to abandon ship. Whenever possible, go

over the side fully clothed. Shoes and clothing may

hinder you while swimming; but in lifeboats, a covering

of any kind offers protection against the effects of sun

and salt water. In a cold climate, wear a watch cap to

keep your head warm. Take along a pair of gloves and

extra clothes if you can. Even in tropical waters you may

feel cool at night because you can do little to keep warm.

Normally, you should leave from whichever side of

the ship is lower in the water; but, if the propellers are

turning, leave from the bow. Leave by the windward

side whenever possible. Leaving from the lee side might

protect you from a stiff wind, but the same wind causes

the ship to drift down on you, often faster than you can

swim. Also, if oil is on the water, you can clear the slick

sooner by swimming into the wind.

Never dive, and do not jump unless you have to. Use

a ladder, cargo net, line, or fire hose. If you must jump,

do so feet first, legs together, and body erect. (First,

check the water so you will not land on debris or on

other personnel.) Except when jumping into flames, be

sure your life preserver is fastened securely, including

the leg straps. If you are wearing a vest-type preserver,

place one hand firmly on the opposite shoulder to keep

the preserver from riding up sharply when you hit the

water (in a long drop, the force of impact might hurt

your chin or neck). Hold your nose with your other

hand. If you are wearing an inflatable preserver, inflate

it after you have entered the water.

In the Water

Once you are in the water, your immediate concern

is to clear the ship as quickly as possible. Before you

rest, you should try to be 150 to 200 yards away from the

ship. When the ship goes down, it may create a strong

whirlpool effect, which might draw you down with the

ship if you are too close. Another advantage of distance

is that you will be safer if an explosion occurs.

After you are safely away from the ship, conserve

your energy. Don’t splash about or shout unnecessarily.

If any danger of underwater explosions exists, float or

swim on your back with your head and chest as far out of

the water as possible. Help your shipmates all you can,

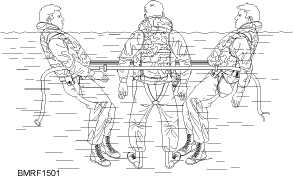

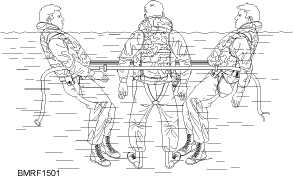

and try to stay in groups (fig. 15-1). Get on a lifeboat, of

course, as soon as you can. In the meantime, grab

anything floatable that comes by, or just relax in the

water. Above all, remain calm!

SWIMMING AND FLOATING.—Check the

chart shown below. It tells you the requirements you

must meet to qualify as a third class, second class, and

first class swimmer.

Meeting the requirements for swimmer third class

won’t help you if you have to swim ½ mile to a lifeboat.

You can see that by qualifying for swimmer second

class, you’d have a better chance to survive. Better yet,

qualifying for swimmer first class gives you the best

chance for survival.

15-2

Student Notes:

Figure 15-1.—Joining life preservers.